Lessons from realism

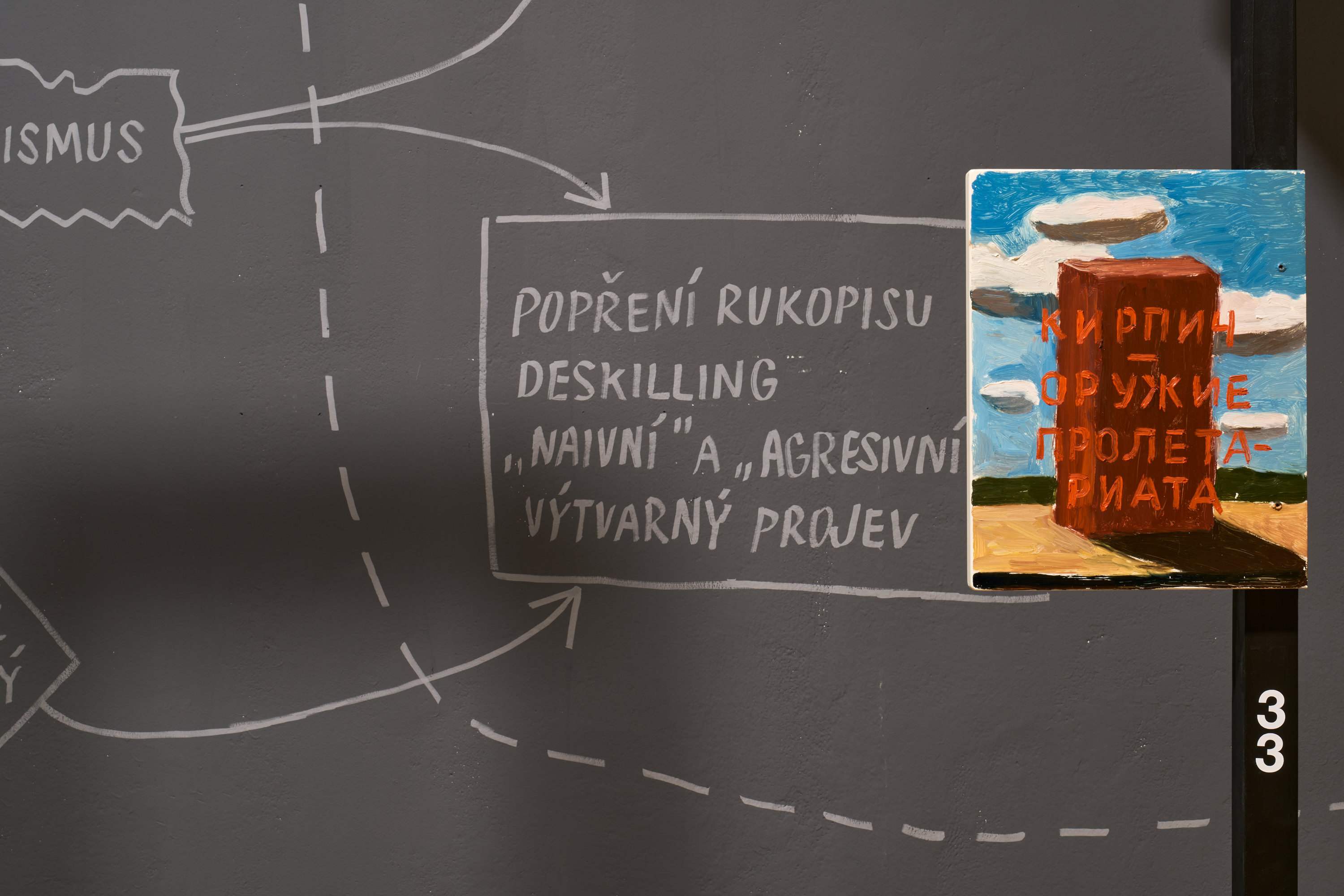

The title of the exhibition may perhaps seem misleading at first. An exhibition whose name includes such an educational appeal might seem a tad categorical. But its aim is not to give anyone lessons in realism, but rather to present the work of someone who has undergone such an educational program. It shows a journey of artistic development based around the experience of truth in art, and Klyuykov’s exhibition provides us with the resumé. Although his artistic expression is self-confident, he is hounded by certain doubts; doubts about the meaning of art and its contemporary social function. He thus presents his work for viewing as a form of case study. It is not a typical journey in the sense of establishing a simple connection and identification with the art of postmodernism as an all-encompassing cannon of western art, but rather marks an attempt at developing an alternative direction based on certain already articulated universalisms. Artistically speaking, this is a minority strategy, which prompts the following generalizations: At this year’s Venice Biennial, Adriano Pedrosa built the exhibition’s main idea on the notion that we are all foreigners. To this, Nicholas Bourriaud ironically replied in his review for Spike that yes, we are all foreigners, but that the exhibition classified such people in a Borgesian manner: Italian immigrants, queer people, those which history has forgotten and left behind, the self-taught, rural communities, artists from the global South, etc. Bourriaud thus wanted to indicate that difference can, on the one hand, include all those marginalized, but it can also fragment ad infinitum. Klyuykov would certainly fit into such a taxonomy. If we attempt to avoid this framing, meaning that we choose not to regard him as a member of a minority of realist painters whom society disregards, we are then left with something like: an emancipatory, anti-capitalist artistic mind, aware of its virtually absent potential for social change in the present, but being exemplary in remaining true to oneself. What do we mean when we say ‘realism’? The exhibition offers various forms, some even ironizing realism itself. We can even doubt whether this is really even realism. If we analyze definitions and historical connections, we rather find a set of related anecdotes. Whoever is able to tell the jokes is at an advantage here, but let’s try it nonetheless. We can start with some basic anecdotes describing the birth of what can, in retrospect, be called realism in classical Greece. Eupompus was a painter who was asked who was his role model in the art of painting; and he answered that he follows nature rather than any master. We can also mention Giorgio Vasari who describes how, in the 13th century, this imperative of emulating nature was revisited somewhere in the hills of Tuscany when, during one of his journeys, the painter Cimabue met a goatherd boy, later named Giotto, who was drawing realistic images of the goats in the sand. Cimabue brought Giotto to his studio and set new standards in the sphere of imitating reality by means of the paintbrush. As writes Karel Teige, since then, features of realism have appeared as particular episodes in the history of art. Teige defines realism as “…an attempt at representing a central projection in accurate proportionality of the reliefs to the objects in space, an attempt at the accurate imitation of nature, meaning the imitation of what we think we see, an attempt at capturing the visible reality in a single view and in an imitative style, so that the reproduction of the objects closely matches how a normal and civilized person would be used to seeing paintings of things they know and the things around them which influence their worldview. To a large degree, this realistic vision matches realistic painting and is the outcome of historical and cultural convention.” This constitutes an important attempt at definition which marks an important shift from the representation of goats. But things are still more complicated. Even the term ‘realism,’ used by Courbet, does not have a clear origin, as he acknowledged in an accompanying text to his exhibition of realist paintings: “The title of Realist was thrust upon me just as the title of Romantic was imposed upon the men of 1830. Titles have never given a true idea of things: if it were otherwise, the works would be unnecessary.” And in order to better illustrate what is and isn’t realistic, we include another anecdote: Courbet considered the depiction of non-contemporary, historical and fictitious scenes and beings as inadmissible, laughing at the authors of Biblical paintings: “Show me an angel and I’ll paint you an angel.” The multivalence and relativity of the concept of realism is further complicated by other developments, such as photography which forced the realists to turn away from mere naturalist imitation. Here we see attempts at raising the demarcation lines between a passive imitation of nature by means of the apparatus on the one side, and the work of a realist/artist as a creative, spiritual activity on the other. But we will not discuss details which may serve to raise any further lines of demarcation. There are many aspects which complicate our understanding of realism. In order to illustrate the deep philosophical problems developing from the principle of simple imitation, lets us narrate one anecdote in the form of a question which a lumberjack asked a Barbizone painter painting in plein air: “Why are you making that oak when it’s already there?” The avantgarde rejected such discussions as so much clutter, but realism came back in a thousand new guises, starting with the innocent realisms filling the apartments of the petit bourgeois, all the way to a new redefinition presented by avantgarde artists, but this time in a more sophisticated manner. Interwar realism does not revisit artistic problems from the nineteenth century, but rather calls for realism as a mimetic strategy, perhaps foreshadowing the postmodern pastiche. In the socialist countries, art in the service of Soviet society leaned towards realism; but not because it reinvigorated old forms, but rather because its new content represented life in revolutionary development. According to Boris Groys, this mimesis focuses on that which does not yet exist, that which is yet to be created. Perhaps another, distinctly Czech, anecdote would be fitting here, narrated by Vincenc Kramář: “Not since the Medieval era has art been this controlled and directly guided by high moral ideals, as in our nascent socialist realism. What does the creativity of a realistic, true rendition and commentary on reality consist of, and what are its means of realization? The answer is: through typification and visual poesis.” There was fragmentation even within socialist realism, and not only in socialist countries. The Austrian Marxist Ernst Fischer writes about it in the postwar era, noting that artists and writers are the seismographs of social change and shock. But he is quick to add that many of them, mostly those with petit bourgeois origins, are not ready to join the working class in order to fulfill the assumptions of their high moral ideas. An example of this tendency towards greater social sensitivity regardless of class origins can be found in the works of the French capitalist and socialist realist Boris Taslitzky who, after returning from the Buchenwald concentration camp, confirms the humanist turn in a much darker anecdote: If I went to hell I would make sketches. In fact, I have lived that experience, I was there and I drew. One of the many unfulfilled possibilities of confronting the art of the two irreconcilable systems during the Cold War was the planned exhibition of curator Jean-Christoph Ammann for documenta 5 in 1972. Ammann gathered contemporary realist American photographers and wanted to engage them with Soviet social realists in an obvious bid to contrast the eastern and western realisms. He aimed to prove that both capitalism and communism are behind these images and the images would correspond to their societies’ respective ideological forms, much like in the novel The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin which came out shortly afterwards. An anecdotal sophism from the book expresses this well: “The sunlights differ, but there is only one darkness.” Postmodern art left behind the urgency practiced in various forms of avantgarde and socialist realism. Fredric Jameson clearly expressed this in an academic anecdote describing the shift in artistic social radicality towards a more distant study of models: “Art provides social information as a symptom. Its specialized apparatus is able to record and capture data with a degree of accuracy unattainable through other modes within the modern experience. When we assemble this data, it models reality in the form of things or substances, and social and institutional ontologies.” We finish this series of anecdotes following the history of realism by shortly mentioning a unique attempt at resuscitating realism in the form of a manifesto (Radical Realist Manifesto). This Manifesto was written in Prague in 2016 with Klyuykov as one of the signatories. It was basically an attempt at breaking free from a postmodern logic of artistic practice by returning to the universalist potential of the artwork, which ought to be comprehensible and “realistic,” i.e. authentic, serious and humanist. Let us cite the first sentence: “For a long time now, art has been in agony. This agony is manifest in the vacuity, nebulosity and incomprehensibility of its form. Because it is unable to mediate its thoughts, it has lost the last scraps of social influence.” Here, we would like to add that the narration of the history of realism by means of anecdotes does not mean that we do not take it seriously. Quite the contrary; what can seem comical to some is merely an expression of the struggle for truth and its representation. “Truth” appears only to those who are able to see it. Nowadays, this requires long preparation and understanding. As Michal Hauser, one of the signatories of the above-mentioned manifesto, notes in his last book: “In modern culture, it is impossible to clearly distinguish what is an original and what is a copy, what is a sign and what is the signified. In the culture of postmodernity, the overproduction of images has reached such a level that reality in the form of the referent or the non-symbolized real loses its autonomous existence and is produced along with a sign or an image. Each attempt at distinguishing the simulation from the real flounders, and the real finally expresses itself as part of the simulacrum.” We tried to sketch here that indefinite genealogy of the relation of reality to truth called realism. We believe that the exhibition reflects this struggle. Echoes of all the anecdotes mentioned can be found in the individual drawings and paintings. We don’t assume that it shows a way out of a postmodern, dissipated culture, nor does it offer an alternative path. Klyuykov is all too conscious of the fact that today’s critique of capitalism cannot produce a true change of state in the order of things. But look closer – perhaps at first sight we are merely unable to notice such an inner critical impulse. For if not, what would be left but one of many exhibitions endlessly exploring further and further differences? What would it all have been about?

Alexey Klyuykov graduated from the studio of Intermediate Confrontation at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague. He has worked as illustrator for various publishers, journals and activist organizations throughout his career. His authorial works mostly work through the medium of painting. He has received the Jindřich Chalupecký Award for his work in collaboration with Vasil Artamonov. He lives and works in Prague.

The anecdotes on realism have mostly been taken from the art history books Tak blízko (So Close) by Marie Klimešová and Hana Rousová and Legenda o umělci (The Legend of the Artist) by Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz, as well as others.

📷: Jan Kolský