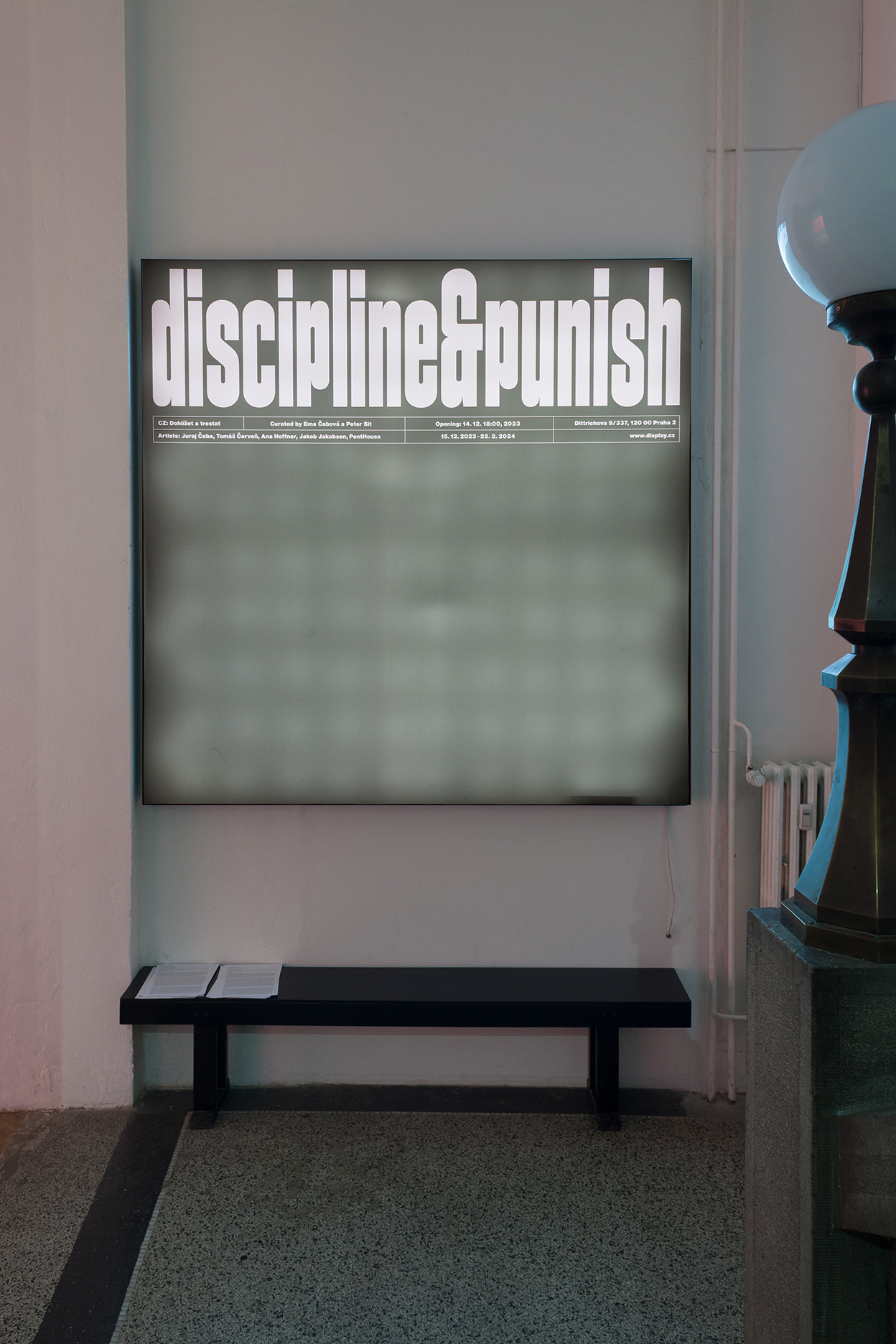

Discipline and punish

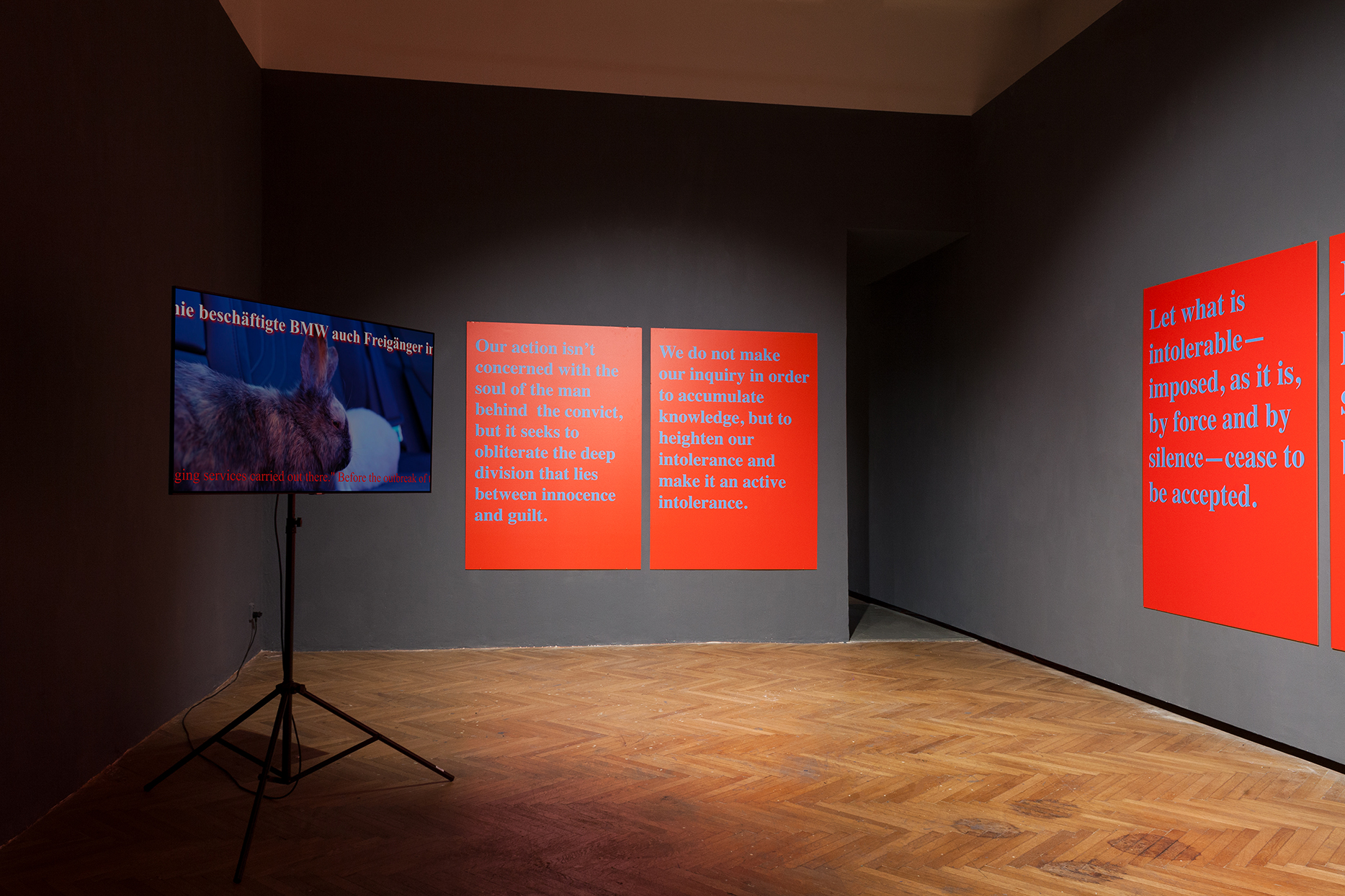

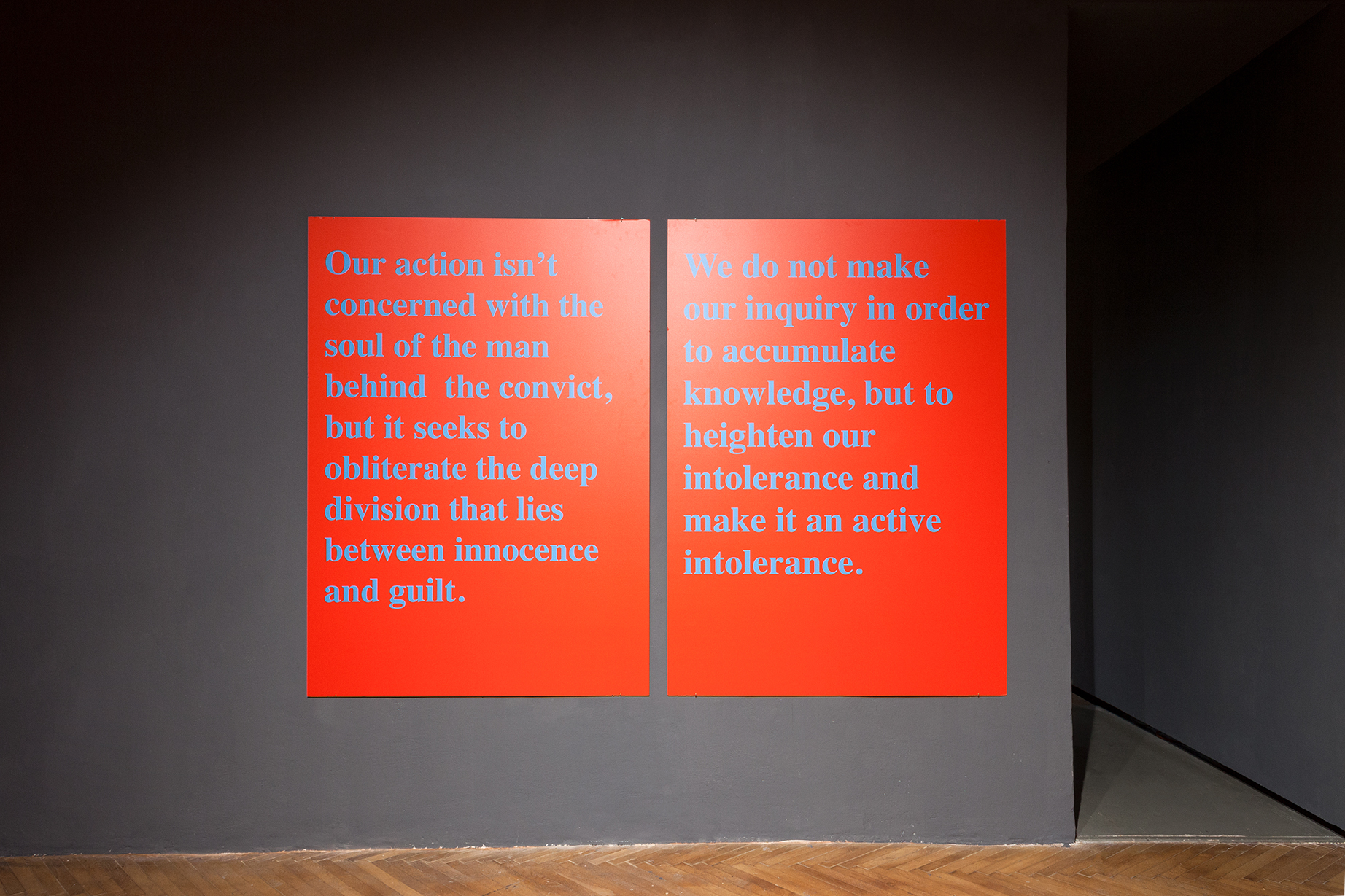

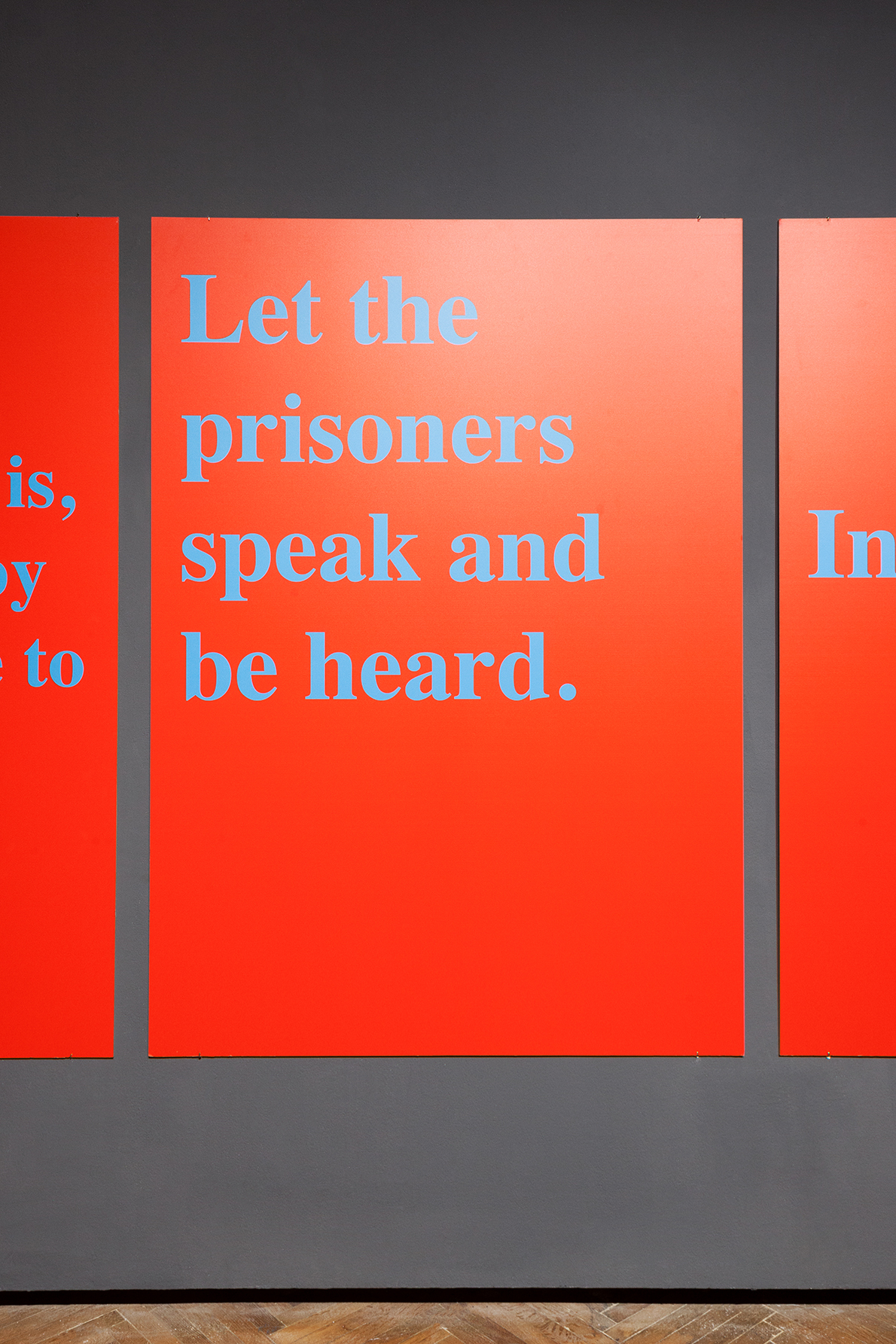

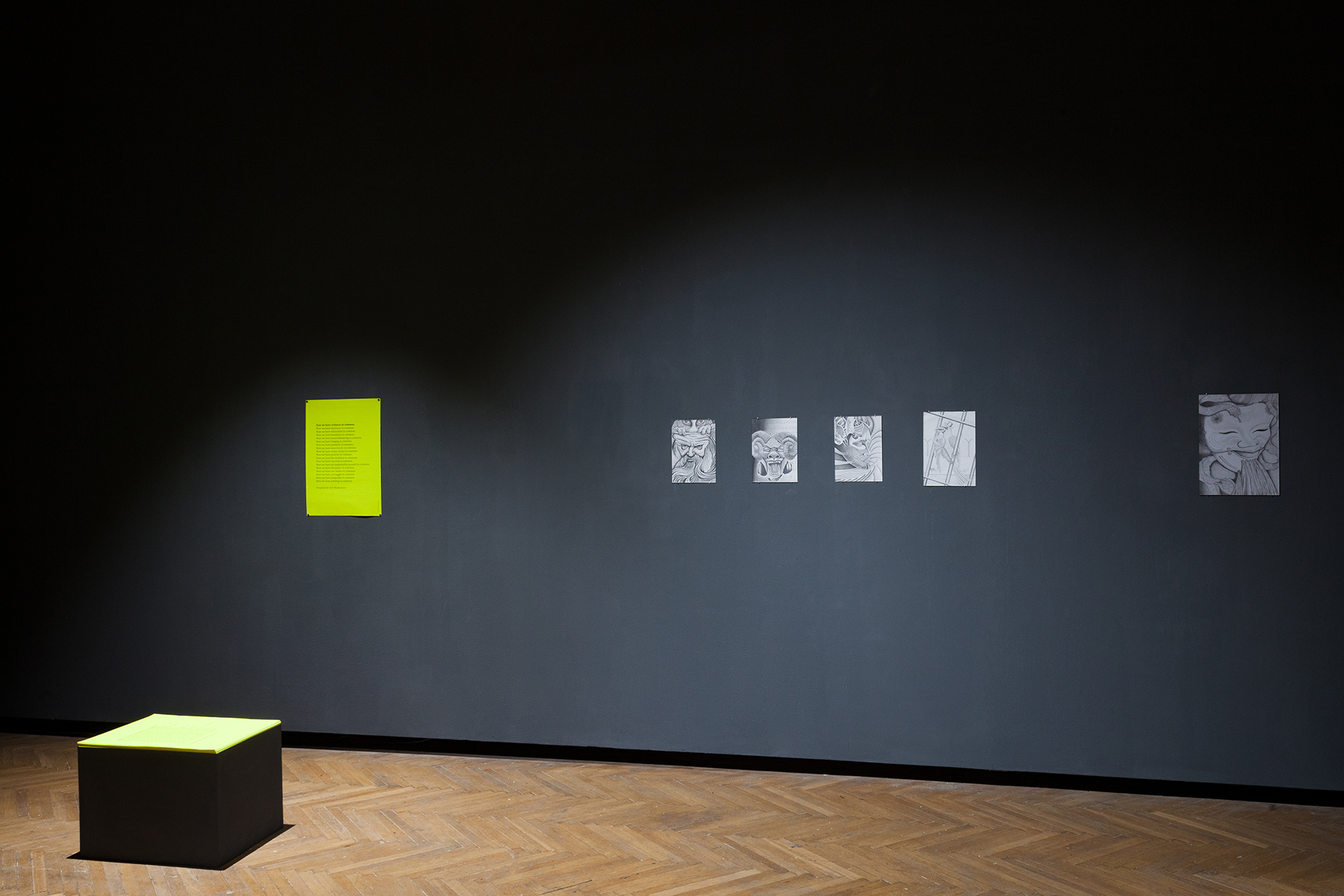

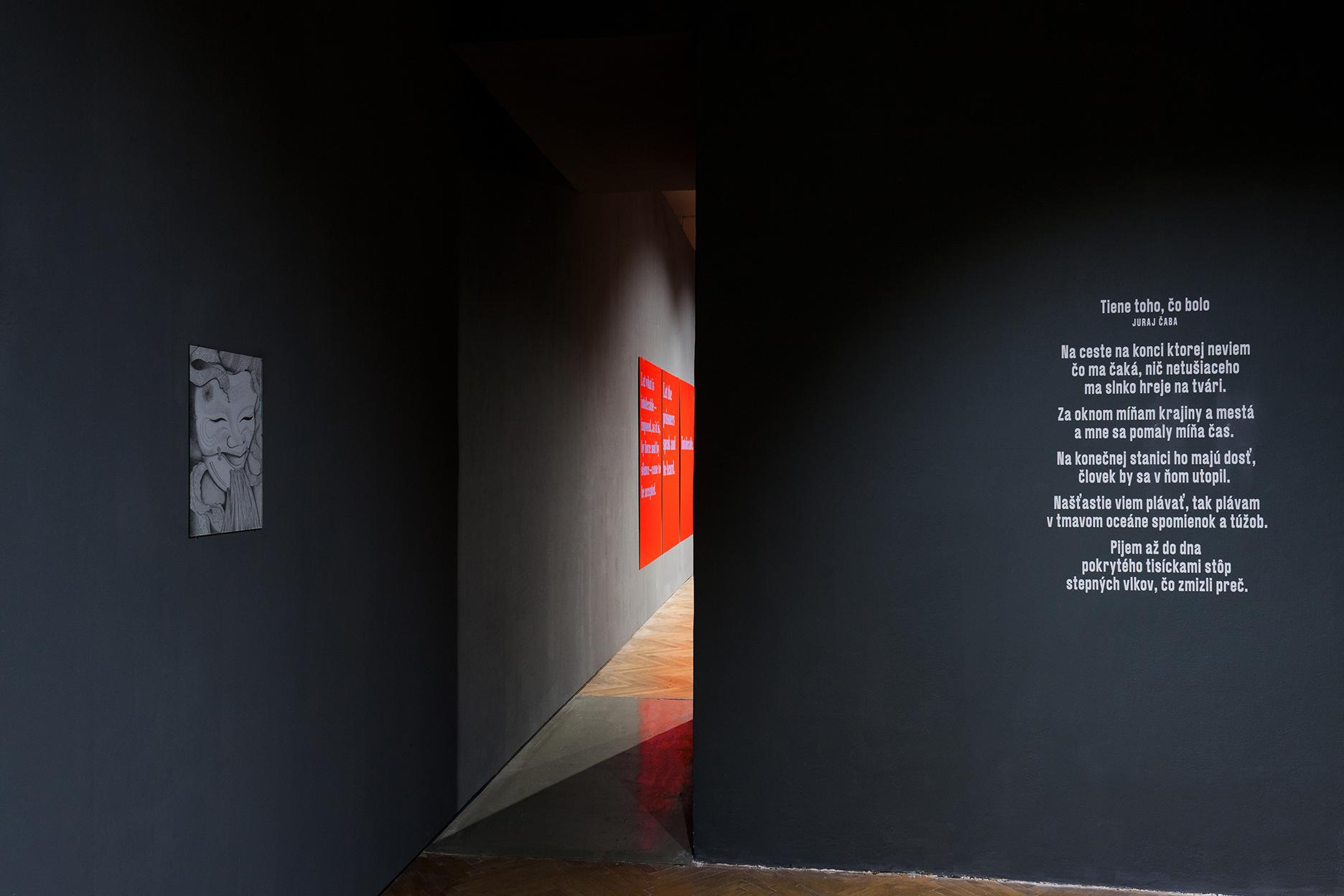

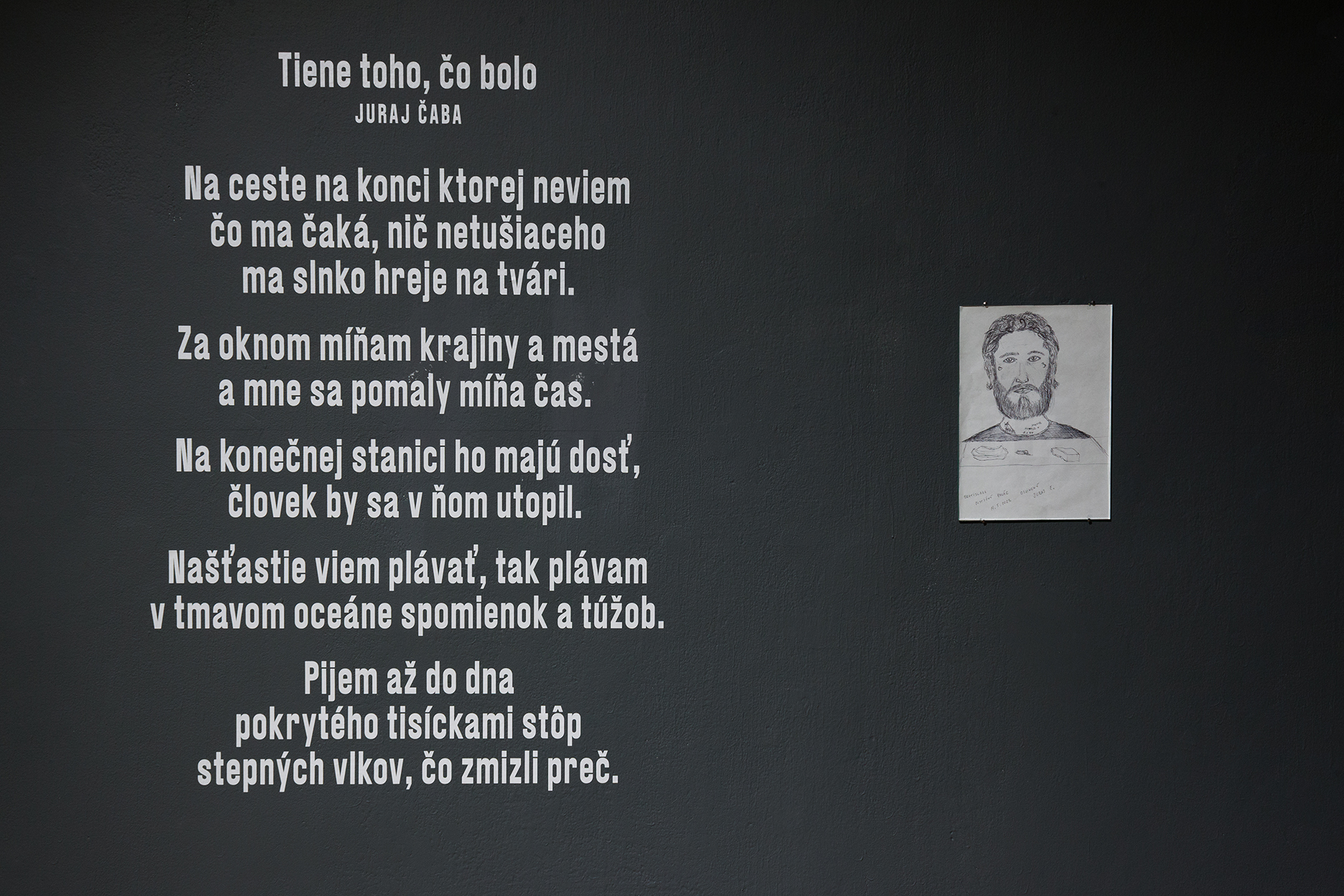

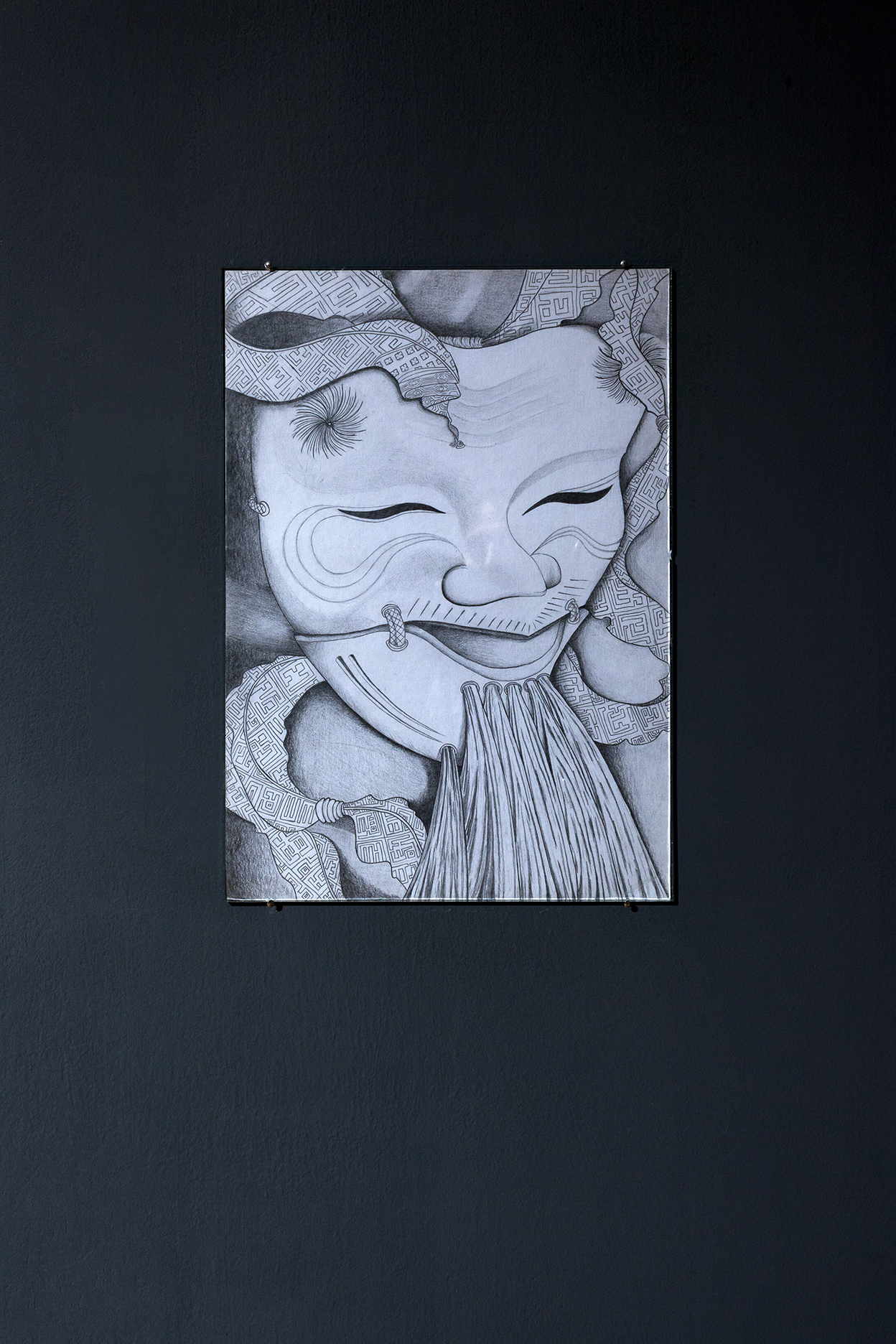

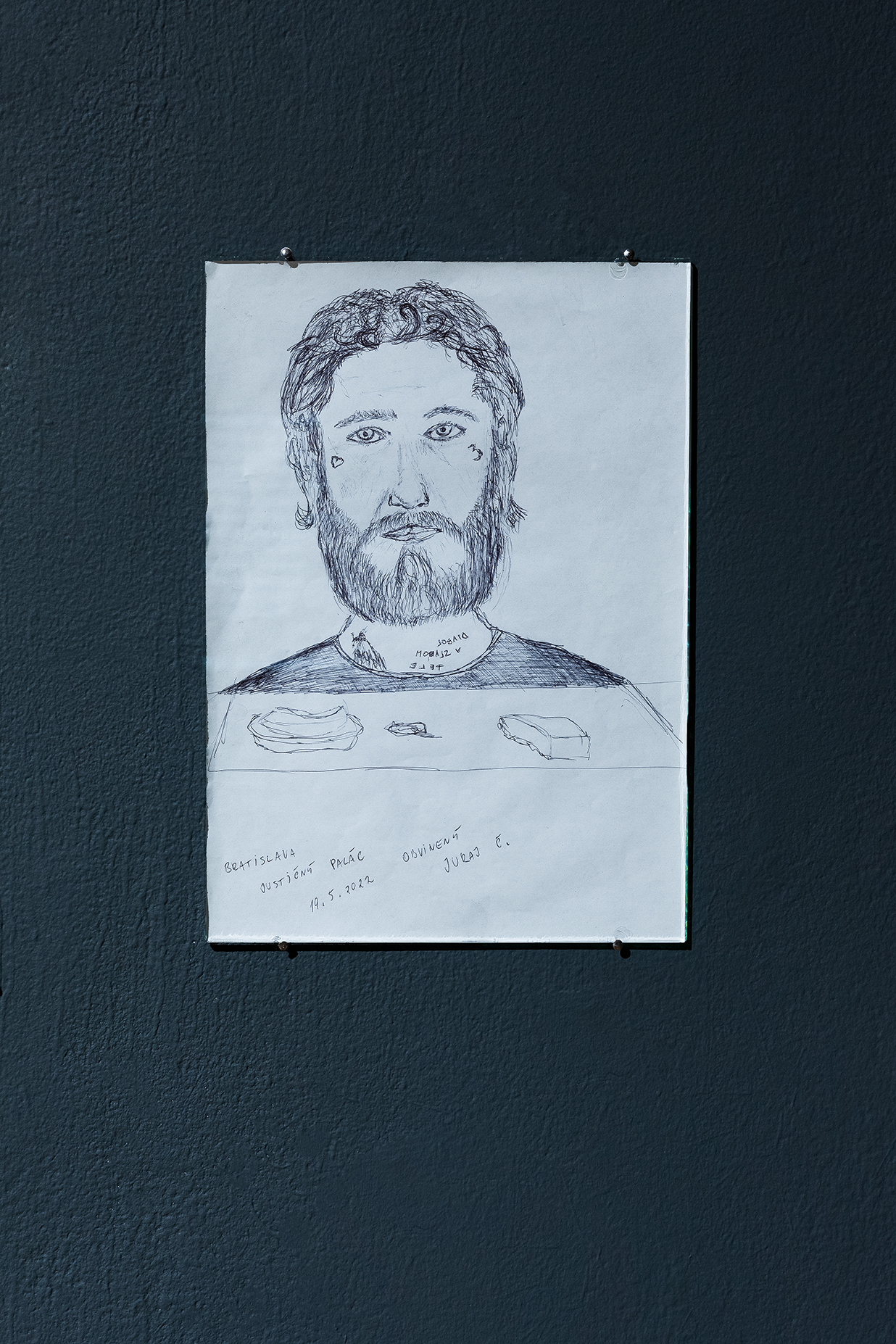

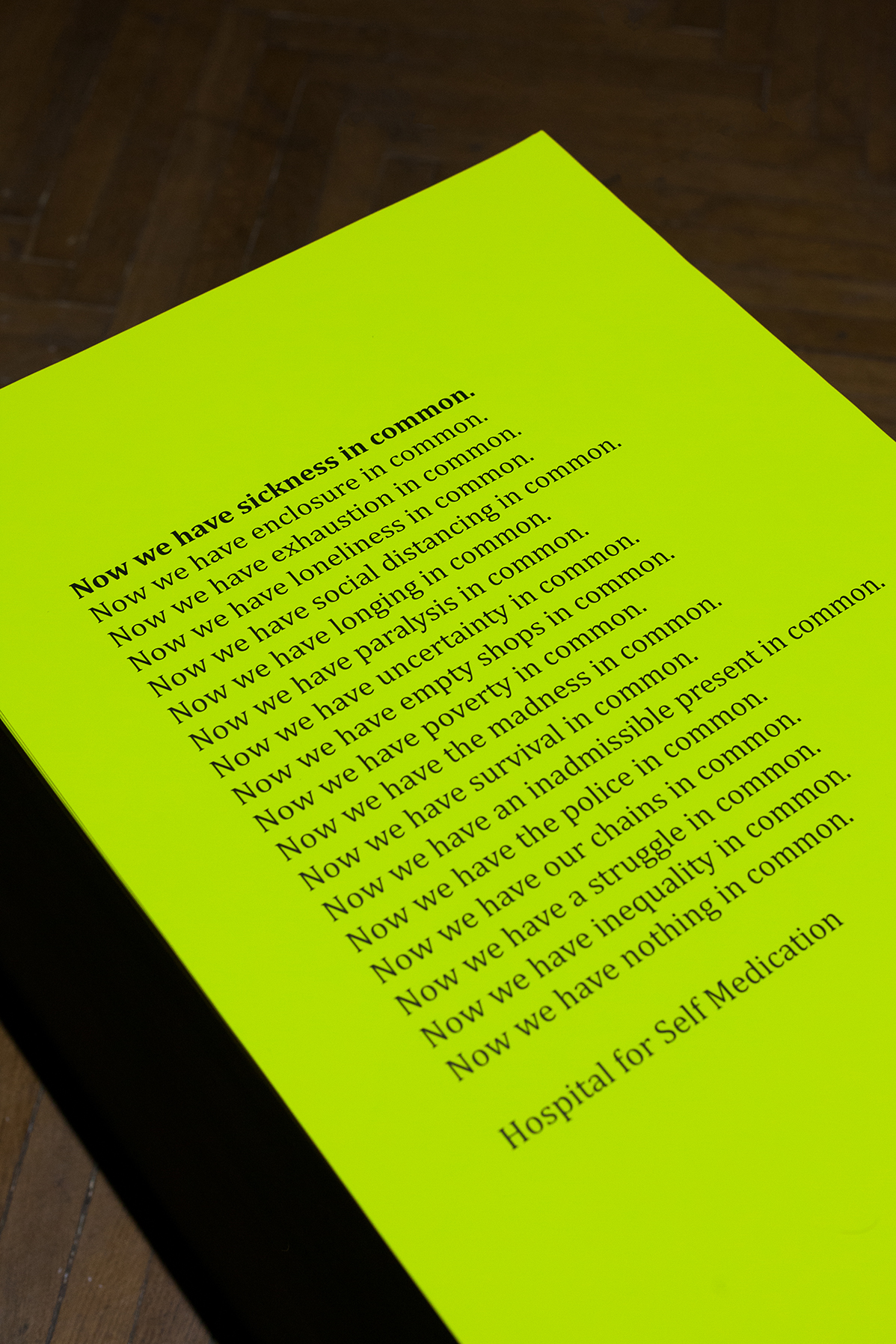

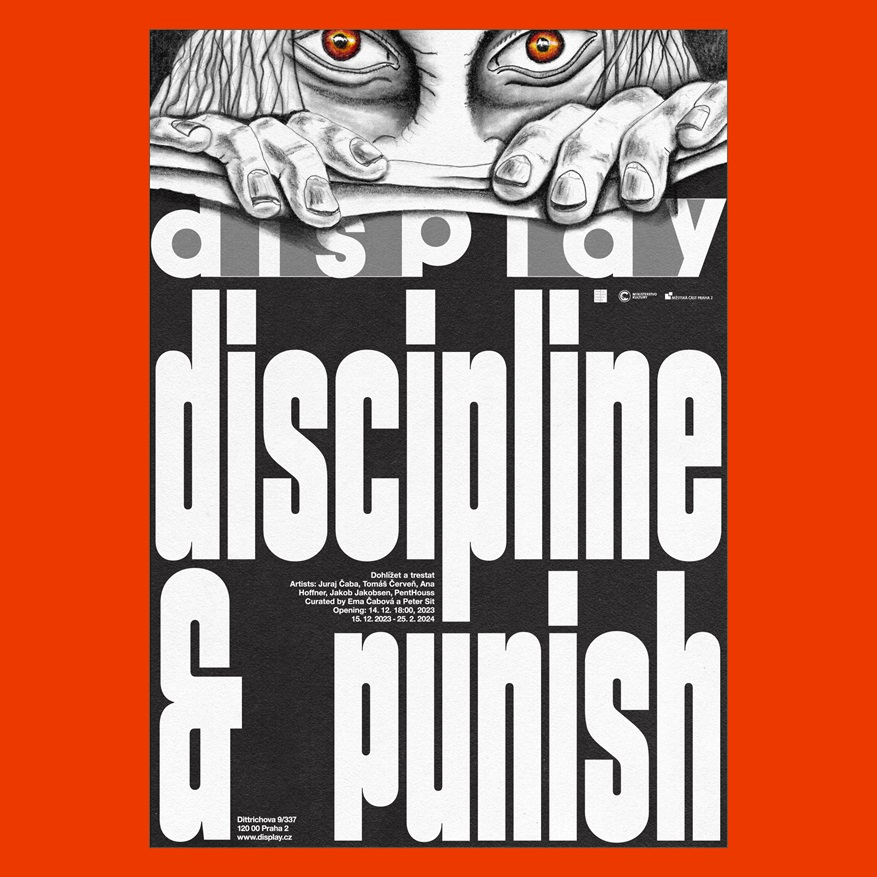

In her book Are Prisons Obsolete?, Angela Davis writes that the concept of a prison “functions ideologically as an abstract site into which undesirables are deposited, relieving us of the responsibility of thinking about the real issues afflicting those communities from which prisoners are drawn in such disproportionate numbers.” Although in this book she writes exclusively about prisons and bases her reasoning on the particular critique of the US prison system, we can interpret her words in wider contexts and relate them to the problematics of prisons globally, and even extend her critique to other forms of institutionalized discipline (which the author herself does through comparing prisons, psychiatric institutions and schools). The exhibition Discipline and Punish addresses complex power and disciplinary systems which have built insurmountable walls around a simplistic narrative determining what and how ought to be punished and who should lose their freedom. These are systems which confidently and without possibility of discussion provide society with a false sense of justice, and a perverse sense of victory over evil. These are systems which want to eliminate resistance at any price and have power over our bodies and minds, whether speaking of prisons or psychiatric clinics. It is not by accident that Angela Davis puts them in one “basket” with schools, asking: “Why do prisons tend to make people think that their own rights and liberties are more secure than they would be if prisons did not exist?” Both types of disciplinary facilities addressed by the exhibition provide such sentiment. Their invisible embrace pacifies intense emotions and experiences of criminality and the psychiatric diagnoses of society living on the margins (i.e. the undisciplined). They provide a simple, understandable, but challenging answer to what we ought to do with people who bring drugs across borders or make others uncomfortable through expressing their “abnormality.” But while such solutions satisfy us, as we can sleep knowing that all the danger is locked up behind the walls of institutions, the number of people diagnosed with psychiatric problems has been rising and criminality remains with us. This exhibition builds on the deep and transformative personal experiences of both curators. The last two years of Ema’s life have been formed by her experience with the Slovakian justice system and prison. After her husband found himself in prison, Angela’s words have acquired a new, pressing honesty. She has been observing, angry and powerless, how society and the prison staff dehumanize and humiliate the inmates and has been listening to the stories of those no one wants to listen to but who are in dire need of such compassion and understanding. That is also why some of these stories, or their fragments, are presented here. Petr’s experience with being hospitalized at a psychiatric clinic significantly transformed him. Aesthetically, the psychiatric institution was more like a prison, as were the doctors’ attitudes. It was a place where a person assumes they did something wrong. One of the things which Petr is interested in is just this sense of guilt, as well as the victimization of persons which often happens to people who have been hospitalized, have visited a psychiatrist or otherwise pay attention to their mental health. And it is based on these experiences that the exhibition thinks about the significance of disciplinary systems which most of us have thought to be only a distant reality. The work of the invited artists reflects various partial aspects of living in a society which disciplines and punishes. Penthouss symbolically and practically metaphorizes the inherent violence connected to institutionalized police in the form of a uniform, Ana Hoffner addresses the issues of prison work and exploitation, the imprisoned Juraj Čaba and Tomáš Červeň present their art works which represent one of the few methods and mechanisms of expressing and processing their loss, and Jakob Jakobsen shows us what can bring us all together and thus serve as a catalyzer for collective action. Together, they point out the absurdity of the existence of these systems, the methods of their operations and the unshakable faith of society that they can “correct,” “cure” or “return people to normal.” Because despite the hard walls which separate us, they are not so far from our lives as may at first seem.